Articles on Organisation

By Dr Norman Chorn

•

February 26, 2021

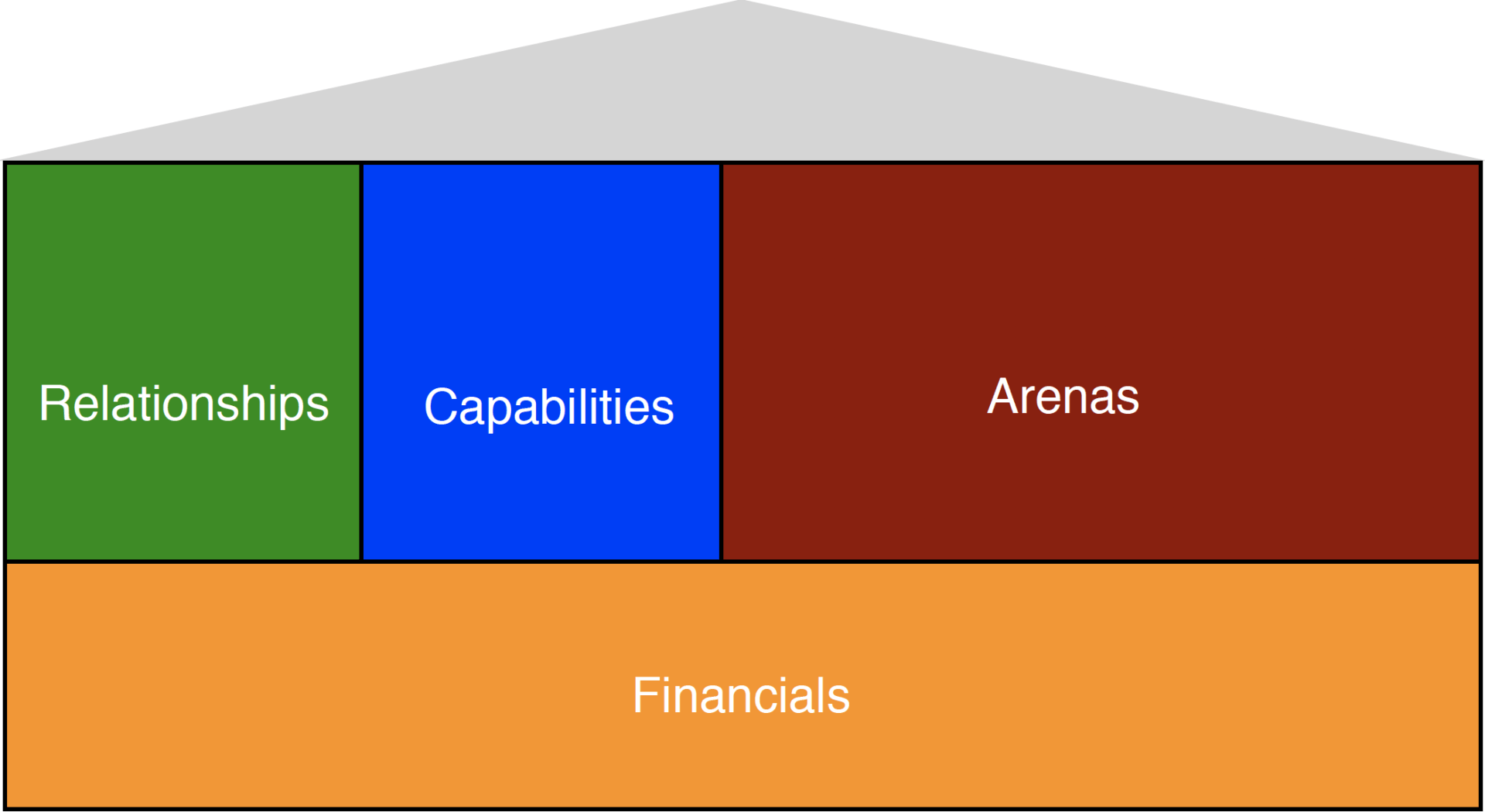

Missing link? One of the keys to succeeding in an uncertain environment is to focus on developing organisational capabilities rather than predicting the future. The trick is to develop these capabilities across a range of futures rather than making a bet on what the future will be like. Obviously, this focus on capability building should be guided by our strategic intent and the manner in which the organisation intends to compete. Traditionally, this task of building organisational capability rests with the HR specialists. Their goal is to link their learning and development programs with business strategy - so that the capabilities align with the organisation’s strategic intent. But this alignment is seldom fully achieved. In fact, during my time in industry and consulting, we have come to regard this alignment between business strategy and HR strategy as somewhat rare and elusive. And poor strategy execution is the major consequence of this lack of alignment. Why does this occur? And what can we do about it? In the main, the breakdown occurs because leaders focuses on strategic intent and competitive advantage, while HR practitioners address the make up of competencies within the organisation. While the connection between competitive advantage and competencies seems clear, there is an important link between the two that is often omitted in organisations. This is the element of organisation design - the manner in which the competencies are configured in order to produce the desired capabilities. What is the relationship between Organisation Design and Capability? HR specialists recognise that competencies are a combination of ability, motivation and style. Capabilities, on the other hand, are achieved by combining the people competencies with organisation design.

By Dr Norman Chorn

•

February 26, 2021

CAN YOU LEAD A COMPLEX ORGANISATION? This reads like a heading from one of those popular questionnaires that purport to test one’s talents or abilities. But it’s not simply a provocative question or teaser to gain your interest. It’s a genuine question about the applicability of conventional leadership approaches to our modern complex organisations. And if they’re not applicable - what can we do about it? The capabilities of modern complex organisations - known as complex adaptive systems - are well understood. They have the capability for: • responding to a changing environment through continuous adaptation • developing new emergent capabilities by learning and innovation • coping with multiple demands and tasks in different parts of the organisation. However, complex adaptive systems also have a number of less ‘desirable’ characteristics. These include: • unpredictability - interventions often produce unexpected outcomes • cause-effect relationships are hard to determine • best practice from other organisations are not readily applicable • errors and failure usually accompany attempts at innovation. Viewed in this light, these characteristics might be thought of as the ‘price’ to be paid for leading a responsive and adaptive organisation. But given these characteristics, leadership models that use conventional performance-management and control systems often fail. Indeed, in many cases, they actually destroy value in these organisations and render them less capable of adaptation and growth. So, if conventional approaches don’t suit complex organisations, what does? Our work suggests new guidelines for effective leadership in a complex organisation. And we identify four tools that may be used to guide these organisations in a way that preserves their innate ability to learn and adapt in their changing environments. ROLE OF A SYSTEM STEWARD ‘Stewardship’ is a concept not often used in the leadership literature. It is usually used to signify a considered and responsible approach to nurturing, growing and managing a set of resources in a sustainable fashion - in this case, an organisation. The term system stewardship is used by Michael Hallsworth where he describes the challenges inherent in complex systems. He argues that a complex system can never be managed or led in a conventional way - it can only be guided and nurtured, if its unique capability to learn and respond is to be retained. We use the metaphor of hosting to imply something similar. That is, leaders cannot really control a complex organisation. Instead, they host it and facilitate the learning and adaptation that takes place within it. As we begin to understand this approach to leadership in a complex environment, three key guidelines emerge: Firstly, leadership in a complex organisation is not so much about improving the performance of the organisation. Instead, it is about creating the conditions in which performance can improve. Secondly, complex environments demand learning, innovation and adaptation. These are not centrally controlled or imposed processes, but rather capabilities that emerge from the organisation itself. Finally, stewardship of the system is the role that leaders play to ensure that this learning, innovation and adaptation occurs. FOUR KEY TOOLS Four key tools can be identified to enable successful stewardship in this way. They are: • Purpose of the organisation - defining the broad outcomes to be achieved (usually not financial) and defining the business of the organisation • Guiding principles by which the organisation will operate - the ‘rules and boundaries’ for the organisation • Performance feedback - understanding how the organisation is making progress towards the achievement of purpose (beyond simple lag-indicators such as profit) • Response to feedback - how leaders respond to possible ‘drift’ away from purpose and / or guiding principles. BECOMING A SYSTEM STEWARD Leading a complex organisation can be described in terms of these four tools of system stewardship. Purpose The key role played by leaders of complex organisation is to robustly define the organisation’s purpose. This means answering the question why. Why does this organisation exist and what is / are the key outcome(s) it seeks? (This is NOT a statement of the financial goals of the organisation - profit is just one of the possible results of an organisation successfully pursuing its purpose). In addition, the purpose would include a statement of which stakeholders and customers are being served, and what value the organisation seeks to provide to them. By defining the purpose clearly, you are defining the overall direction in which the organisation should head. See the table below for an example. Guiding principles These principles provide the boundaries, rules and framework within which the organisation needs to operate. Where the organisation and environment are highly complex, high levels of adaptation are required. Consequently, these boundaries will be fairly general and will encourage learning and adaptation. An example is the provision of financial planning services to individual families. Here the organisation might set guidelines relating to the types of investments considered inappropriate and the maximum level of debt / risk for the client. The financial planner is then given the scope to develop an innovative package the suits the individual family’s needs and goals. Conversely, where the organisation’s response needs to be highly uniform and stakeholders’s requirements are similar, the boundaries can be more explicit and extensive. A good example of this might be a network of fast-food outlets providing low cost, nutritious meals. In this case, the organisation might have a framework that determines the combination of ingredients and food types in each meal, as well as the total cost of each meal. Each outlet is then left to determine how to operate within those guidelines by using local ingredients and suppliers. Performance feedback The feedback process is about tracking the progress made towards the achievement of the organisation’s purpose and goals. Importantly in complex organisations, simply monitoring KPIs is not enough. Complexity requires that the leader seeks to understand how the outcomes are being achieved, not simply the results that are produced. In many cases, this may require a more informal, inquiring process into the functioning of the organisation. An analogy might be a netball coach who cannot judge the performance of her team by simply monitoring the win-loss ratios. She has to watch the games and see how the players and team are performing. She will observe different parts of the game - defence and attack, for example - and construct a picture of how the team is working together overall. This procedure of understanding the processes whereby the complex organisation achieves its purpose and goals is vital to obtaining feedback about performance. Only in this way can the leader create the conditions in which performance can improve. Response to feedback The reaction to feedback is a critical process in leading complex organisations - provided the feedback process has been set up correctly. Based on the feedback, the response may range from subtle signalling to direct intervention. In general, the greater the complexity and the need for learning and adaptation, the more indirect the response should be. Some of the indirect responses include: • signalling: where the leader signals her preferences by way of presentations, blogs and informal communication through the organisation • increasing transparency: where the managers and staff are subject to open questioning and challenge about their decisions - they make the decisions themselves, but have to be prepared to be challenged on them • capacity building: where the organisation builds skill and capability in those areas where direction should be changed or performance improved • making connections: where the leader enables connections with outside bodies or between parts of the organisation in order to share thinking and spread ideas. An example is an organisation that has a cumbersome capital expenditure process that slows its response to a changing environment. The leaders begin to comment and discuss this challenge explicitly, and then include these views in their internal communications. Capex approvals are made more transparent by discussing them openly at regular executive meetings. Finally, outside experts are invited into the organisation to discuss the issue and to facilitate an exercise whereby management can explore it in greater depth.

By Norman Chorn

•

March 27, 2023

In my previous article "Accelerate Performance with Strategic Alignment - Define the logic of your strategy", we demonstrated the alignment between the market and business strategy by matching the logic of the market with the logic of the strategy. The Explore logic emphasises a market where customers seek new solutions for emerging requirements. The strategy responds by exploring new opportunities and driving for growth. The Exploit logic occurs in a more stable market where customers seek lower costs and reliability of supply. The appropriate strategy focuses on operational efficiency and building close customer relationships. Culture is key to shaping the capabilities of the business to successfully implement strategy . It drives the way that people behave, decisions are made and actions are taken. It determines, therefore, the strategy that is actually realised in the market, as opposed to that which is merely intended. We make a key distinction between the desired culture and the appropriate culture. The desired culture is what people may choose because it sounds attractive and in vogue. However, the appropriate culture is the culture that is required to successfully implement the chosen strategy. Often, these can be different. For example, people might seek to develop a culture that is ‘innovative’, ‘flexible’ and ‘empowering’, but this may not be the appropriate culture needed to successfully implement the business strategy. DEVELOP THE APPROPRIATE CULTURE FOR YOUR STRATEGY Developing the appropriate culture requires a deliberate emphasis on certain cultural attributes and making trade-offs on others. As we will see, the attributes that are traded off are usually the opposites of those that are emphasised.

By Norman Chorn

•

March 27, 2023

In Part 1 "How to Accelerate Performance with Strategic Alignment - Understand the Logic of the Market" we outlined different market conditions and defined them in terms of two overarching logics — Exploring and Exploiting . To briefly recap, an Exploring logic is one where customers are seeking new solutions for emerging needs. It’s all about change and action. An Exploiting logic occurs in a more stable market in which the issues are about lowering costs and working collaboratively with customers. It’s a market that focuses on stability and cohesion. FORCES THAT SHAPE YOUR STRATEGY Clearly, it is one of these two logics — or a combination of both — that will shape your strategy as you operate in these markets. See figure 1 below that describes how these logics will form your business strategy:

By by Dr Norman Chorn

•

March 27, 2023

Do you know what will help your organisation perform better? In the last 30 years of research a key finding is to ensure your strategy is right for the market, and then to have a culture and leadership style to reinforce this. But what’s the code that unlocks this alignment of market, strategy, culture, and leadership? What is the approach that outlines how these key elements fit together? If you had a chance to attend or watch the replay of my live webinar ‘How Leaders Align Culture with the Logic of Their Strategy?' I discussed an approach to create this alignment. Following on from this topic, I thought it would be of benefit, to share my key insights of “Strategic Alignment” methodology in greater detail and I will do this over the next few articles. This will help you and your organisation create strategic fit between your organisation and the market. Forces that shape the market and strategy We begin by outlining the timeless forces that explain the patterns behind behaviour, decisions, initiatives and plans. Extensive research shows that we can apply these same forces to explain the overarching logic of how a market operates and what customers want. See Figure 1 below - The forces that shape behaviours, decisions, initiatives and plans

By by Dr Norman Chorn

•

September 28, 2022

What drives organisational performance There is a wide range of views on the definition of organisational performance. Profitability? Market share? Good products? Despite the lack of a common measure for performance, the question of what drives performance is more easily answered. We have given up the search for the strategy, culture or style that produces the best performance in any condition. Instead, it seems more sensible to recognise that any strategy is only appropriate in a given set of market or competitive conditions. Similarly, we realise that a given culture or leadership style is only appropriate in a given strategic situation. While this basic principle is easily understood, how can it be applied? We think driving organizational performance may lie in the concept of “ strategic fit ”. What is Strategic Fit and How Does it 'Fit In'? Strategic “fit” considers the degree of alignment between your strategy, culture and leadership style. In this sense, alignment refers to the “appropriateness” of the elements to one another. Research reveals that superior performance (measured in a variety of ways) is associated with high degrees of alignment between strategy and culture — ie: a good “fit” between strategy and culture. This is explained by the fact that culture has a significant influence on the organisation’s capabilities in two ways: By acting as a filter to constrain strategic options to those that are compatible with the existing culture (1) [ 1] By requiring cultural change to enable the organisation to effectively implement its strategy (2) [ In both cases, we see that the “fit” between culture and strategy is closely associated with the organisations ability to execute strategy and, therefore, improve an organisation’s performance. Leadership has a critical role to play in this “fit’ between culture and strategy. Not only does leadership influence and guide the overall strategy, culture is also shaped by the style and key behaviours of leaders in the organisation. 3 Steps Leaders Can Take to Strategically Align Culture With The Business Strategy Clearly define the business strategy with respect to “how we will win” in the market Identify the key elements of the culture to support the strategy Adopt a leadership style that will actively shape the required culture. These steps are further outlined below. 1. Clearly Define The Business Strategy With Respect to 'How we Will Win' in The Market The purpose of strategy is to achieve some form of competitive advantage. Therefore, strategy should answer the question of “how will we win?”, or “what do we do to earn our customers’ business in this market?”. Competitive advantage is achieved when the business has a pronounced focus on the source of competitive advantage. Focus is achieved through a purposeful over-allocation of resources to a particular set of initiatives, rather than evenly spread through all initiatives. Focus is different to balance – it is a deliberate imbalance of resource allocation. There are 4 focused pathways to choose from to create competitive advantage in strategy. These are represented in the diagram below by individual colours. Recognise that your strategy may have elements of all four pathways — but there should be clear dominance in one to reflect the required focus.

By by Norman Chorn

•

February 15, 2022

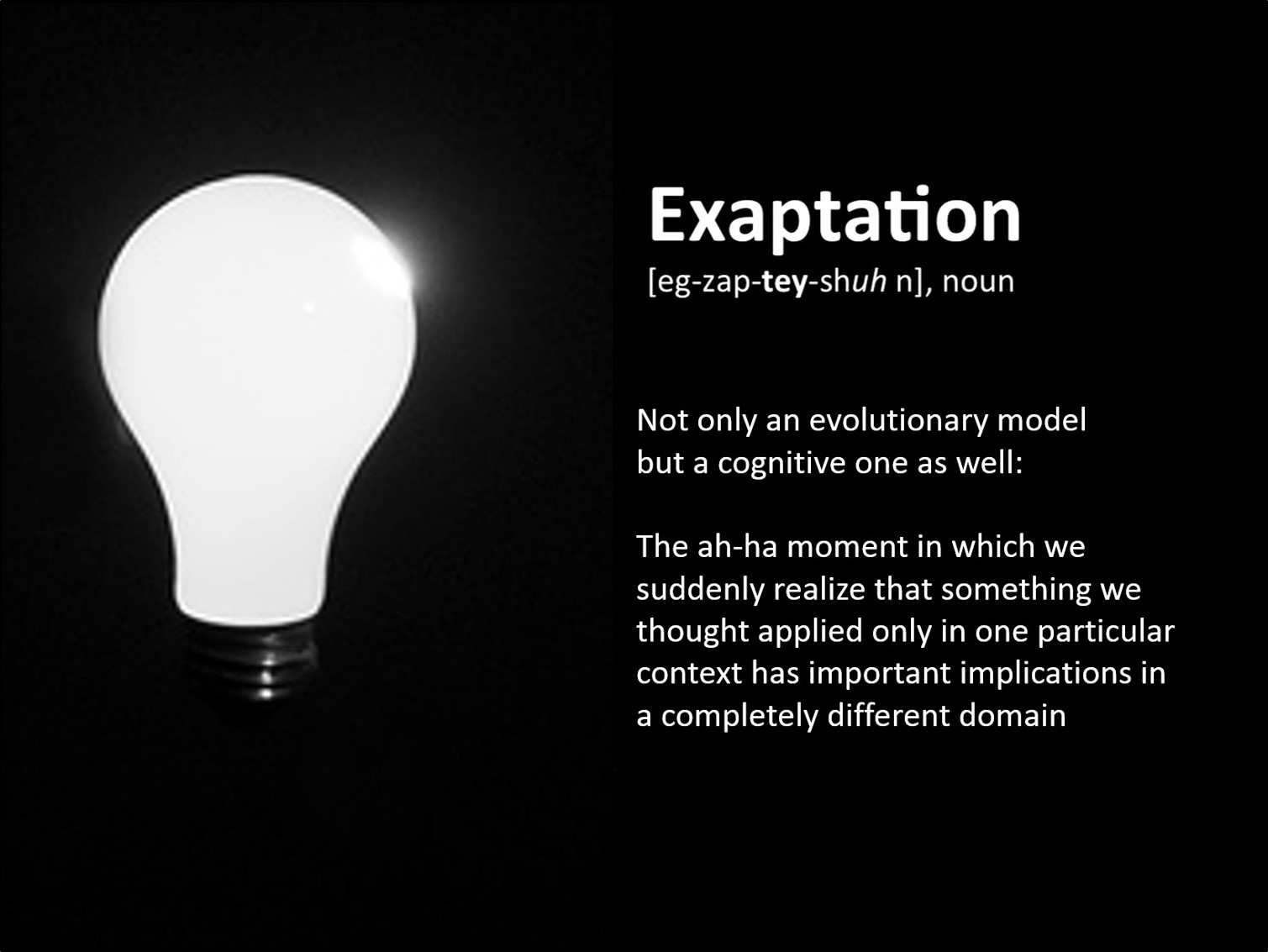

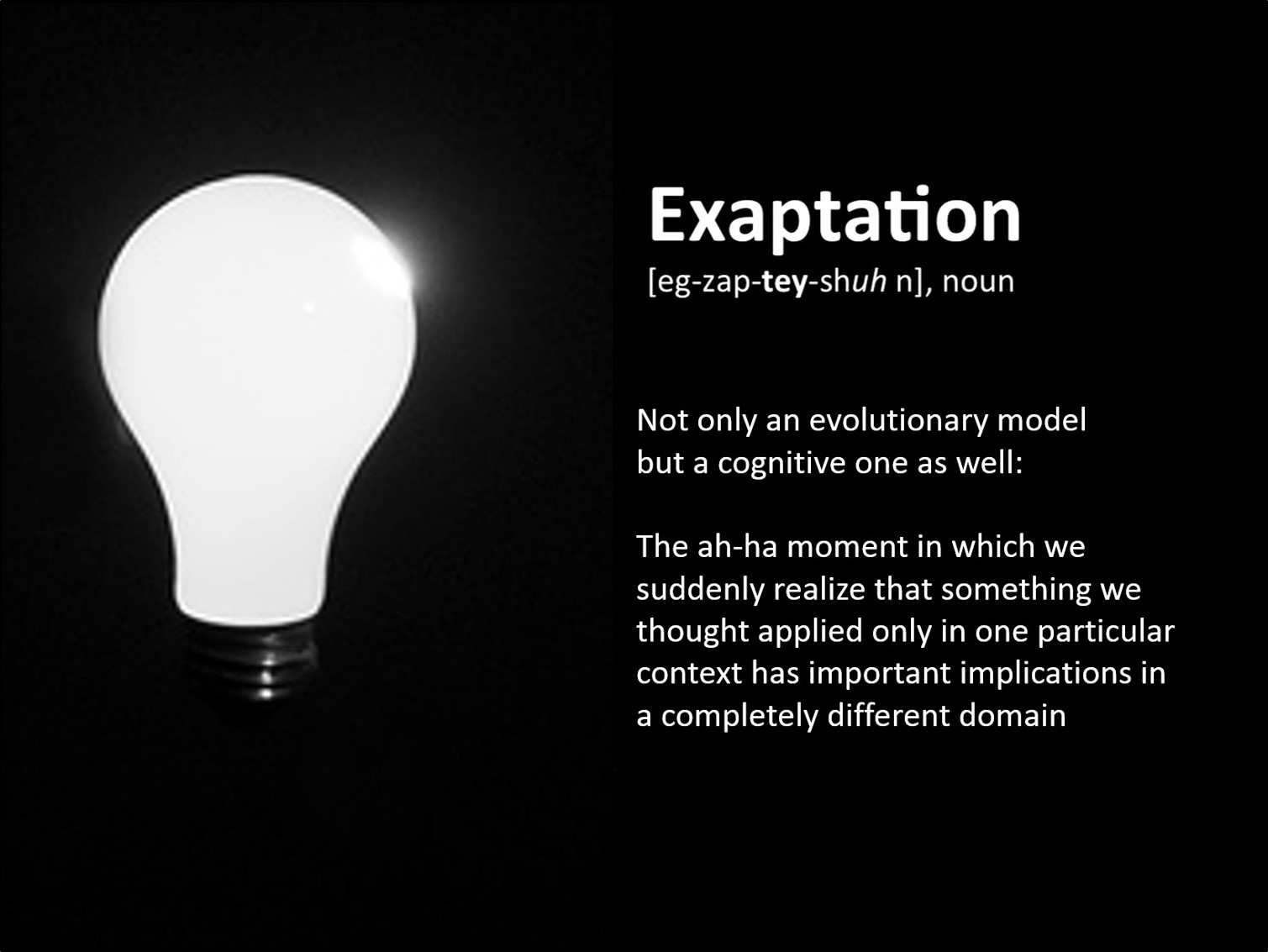

This article discusses the principles that drive organisational resilience. From research conducted the development of organisational resilience is not an evolutionary process. It is developed by co-opting and adapting organisational functions for purposes other than which they were created. This process is called “exaptation”.

By by Norman Chorn

•

December 6, 2021

Agile Methodolgies Offer Much There is much to like about the Agile approach when you read about it and listen to others sing its praises. It embraces adaptability, flexibility, speed of response and continuous interaction with the customer. Agile can be defined as the ability to rapidly and efficiently adapt to changes in our environment. Agile seems ideally suited to our VUCA ( 1 ) environment that is characterised by constant change and disruptions. Our traditional mechanistic organisations are not enabling the natural creativity of people, and their top down, slow strategy processes cannot keep up with the demands of the fast-moving environment. In contrast, Agile offers rapid decision-making and learning by way of its iterative processes and adaptability. But let’s examine the concept a little more closely to see how it copes with all the aspects of our VUCA environment — particularly the inherent complexity that makes strategy and decision-making that much more challenging.

By Norman Chorn

•

March 27, 2023

In my previous article "Accelerate Performance with Strategic Alignment - Define the logic of your strategy", we demonstrated the alignment between the market and business strategy by matching the logic of the market with the logic of the strategy. The Explore logic emphasises a market where customers seek new solutions for emerging requirements. The strategy responds by exploring new opportunities and driving for growth. The Exploit logic occurs in a more stable market where customers seek lower costs and reliability of supply. The appropriate strategy focuses on operational efficiency and building close customer relationships. Culture is key to shaping the capabilities of the business to successfully implement strategy . It drives the way that people behave, decisions are made and actions are taken. It determines, therefore, the strategy that is actually realised in the market, as opposed to that which is merely intended. We make a key distinction between the desired culture and the appropriate culture. The desired culture is what people may choose because it sounds attractive and in vogue. However, the appropriate culture is the culture that is required to successfully implement the chosen strategy. Often, these can be different. For example, people might seek to develop a culture that is ‘innovative’, ‘flexible’ and ‘empowering’, but this may not be the appropriate culture needed to successfully implement the business strategy. DEVELOP THE APPROPRIATE CULTURE FOR YOUR STRATEGY Developing the appropriate culture requires a deliberate emphasis on certain cultural attributes and making trade-offs on others. As we will see, the attributes that are traded off are usually the opposites of those that are emphasised.

By Norman Chorn

•

March 27, 2023

In Part 1 "How to Accelerate Performance with Strategic Alignment - Understand the Logic of the Market" we outlined different market conditions and defined them in terms of two overarching logics — Exploring and Exploiting . To briefly recap, an Exploring logic is one where customers are seeking new solutions for emerging needs. It’s all about change and action. An Exploiting logic occurs in a more stable market in which the issues are about lowering costs and working collaboratively with customers. It’s a market that focuses on stability and cohesion. FORCES THAT SHAPE YOUR STRATEGY Clearly, it is one of these two logics — or a combination of both — that will shape your strategy as you operate in these markets. See figure 1 below that describes how these logics will form your business strategy:

By by Dr Norman Chorn

•

March 27, 2023

Do you know what will help your organisation perform better? In the last 30 years of research a key finding is to ensure your strategy is right for the market, and then to have a culture and leadership style to reinforce this. But what’s the code that unlocks this alignment of market, strategy, culture, and leadership? What is the approach that outlines how these key elements fit together? If you had a chance to attend or watch the replay of my live webinar ‘How Leaders Align Culture with the Logic of Their Strategy?' I discussed an approach to create this alignment. Following on from this topic, I thought it would be of benefit, to share my key insights of “Strategic Alignment” methodology in greater detail and I will do this over the next few articles. This will help you and your organisation create strategic fit between your organisation and the market. Forces that shape the market and strategy We begin by outlining the timeless forces that explain the patterns behind behaviour, decisions, initiatives and plans. Extensive research shows that we can apply these same forces to explain the overarching logic of how a market operates and what customers want. See Figure 1 below - The forces that shape behaviours, decisions, initiatives and plans

By by Dr Norman Chorn

•

September 28, 2022

What drives organisational performance There is a wide range of views on the definition of organisational performance. Profitability? Market share? Good products? Despite the lack of a common measure for performance, the question of what drives performance is more easily answered. We have given up the search for the strategy, culture or style that produces the best performance in any condition. Instead, it seems more sensible to recognise that any strategy is only appropriate in a given set of market or competitive conditions. Similarly, we realise that a given culture or leadership style is only appropriate in a given strategic situation. While this basic principle is easily understood, how can it be applied? We think driving organizational performance may lie in the concept of “ strategic fit ”. What is Strategic Fit and How Does it 'Fit In'? Strategic “fit” considers the degree of alignment between your strategy, culture and leadership style. In this sense, alignment refers to the “appropriateness” of the elements to one another. Research reveals that superior performance (measured in a variety of ways) is associated with high degrees of alignment between strategy and culture — ie: a good “fit” between strategy and culture. This is explained by the fact that culture has a significant influence on the organisation’s capabilities in two ways: By acting as a filter to constrain strategic options to those that are compatible with the existing culture (1) [ 1] By requiring cultural change to enable the organisation to effectively implement its strategy (2) [ In both cases, we see that the “fit” between culture and strategy is closely associated with the organisations ability to execute strategy and, therefore, improve an organisation’s performance. Leadership has a critical role to play in this “fit’ between culture and strategy. Not only does leadership influence and guide the overall strategy, culture is also shaped by the style and key behaviours of leaders in the organisation. 3 Steps Leaders Can Take to Strategically Align Culture With The Business Strategy Clearly define the business strategy with respect to “how we will win” in the market Identify the key elements of the culture to support the strategy Adopt a leadership style that will actively shape the required culture. These steps are further outlined below. 1. Clearly Define The Business Strategy With Respect to 'How we Will Win' in The Market The purpose of strategy is to achieve some form of competitive advantage. Therefore, strategy should answer the question of “how will we win?”, or “what do we do to earn our customers’ business in this market?”. Competitive advantage is achieved when the business has a pronounced focus on the source of competitive advantage. Focus is achieved through a purposeful over-allocation of resources to a particular set of initiatives, rather than evenly spread through all initiatives. Focus is different to balance – it is a deliberate imbalance of resource allocation. There are 4 focused pathways to choose from to create competitive advantage in strategy. These are represented in the diagram below by individual colours. Recognise that your strategy may have elements of all four pathways — but there should be clear dominance in one to reflect the required focus.

By by Norman Chorn

•

February 15, 2022

This article discusses the principles that drive organisational resilience. From research conducted the development of organisational resilience is not an evolutionary process. It is developed by co-opting and adapting organisational functions for purposes other than which they were created. This process is called “exaptation”.

By by Norman Chorn

•

December 6, 2021

Agile Methodolgies Offer Much There is much to like about the Agile approach when you read about it and listen to others sing its praises. It embraces adaptability, flexibility, speed of response and continuous interaction with the customer. Agile can be defined as the ability to rapidly and efficiently adapt to changes in our environment. Agile seems ideally suited to our VUCA ( 1 ) environment that is characterised by constant change and disruptions. Our traditional mechanistic organisations are not enabling the natural creativity of people, and their top down, slow strategy processes cannot keep up with the demands of the fast-moving environment. In contrast, Agile offers rapid decision-making and learning by way of its iterative processes and adaptability. But let’s examine the concept a little more closely to see how it copes with all the aspects of our VUCA environment — particularly the inherent complexity that makes strategy and decision-making that much more challenging.