A Controversial Starting Point

I know that several readers will find my opening argument quite controversial - after all, it goes against much of the conventional wisdom about effective organisations.

But, effective organisations display more focus than they do balance. So whatʼs the difference between focus and balance anyway, and why is it important?

The question is best addressed by examining the origins of competitive advantage in organisations - a concept that makes sense for both profit and not-for-profit organisations. I argue that in order for an organisation to develop competitive advantage, it has to pursue elements of focus in its resource allocation - and this is, in effect, an imbalance.

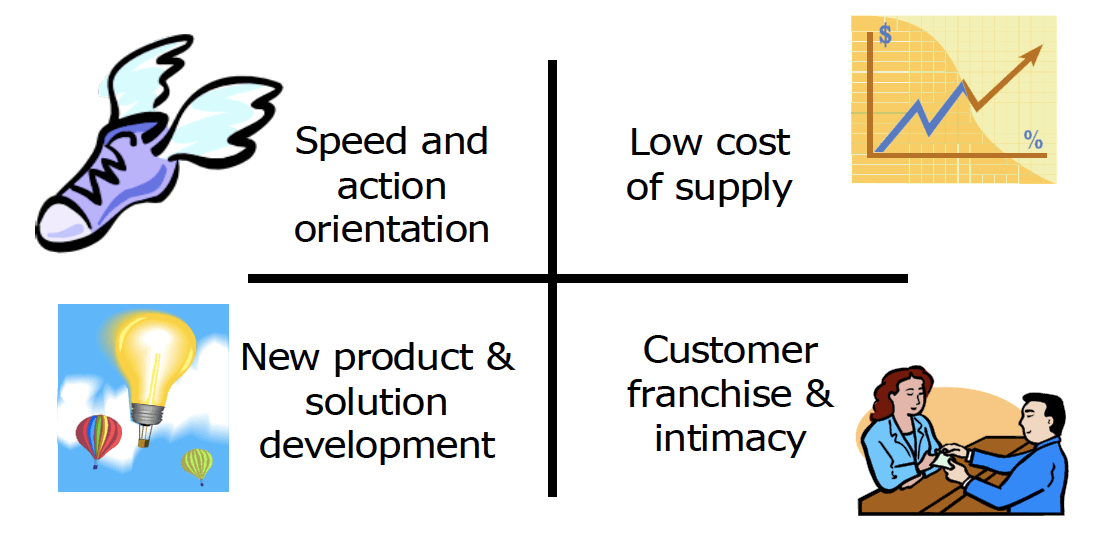

Pathways to Competitive Advantage

As the diagram below depicts, there are four generic sources of competitive advantage within organisations. Each pathway makes specific demands upon the resource configuration of the organisation - and these are not readily changeable in the short term.

This means that an organisation adopting a speed and action orientation posture will require a flat organisation with decentralised decisions and high degrees of empowerment.

An organisation which elects to compete as the lowest cost supplier will require a more highly structured design with strong controls and process rules. The customer franchise and intimacy platform requires a premium on team work, shared values and collaborative decision-making; while an organisation competing on innovation and new product development will have a fluid, network-style organisation with high levels of individual accountability and performance.

These resource configurations can be mixed but a simple examination will show that they represent trade-offs and compromises. For example, the speed posture is significantly different to the customer intimacy posture - and they are not easily combined in the same part of the organisation.

In other words, when a part of the organisation focuses on speed and action as its particular pathway to competitive advantage, it makes a series of deliberate decisions to over-allocate effort in certain areas of the organisation at the expense of others.

This is in effect, an imbalance of one set of factors over another. Hence, focus actually resembles an imbalance in the organisation.

Weʼre not suggesting that all is forsaken in the quest for focus - there are obviously elements of all issues in any organisation. But there is a definite focus in favour of some issues over others.

A Portfolio of Focuses

So, how do you achieve coverage of different focuses across the organisation? For example, how do you pursue customer intimacy in one market segment and speed to market in another?

Well, the answer is NOT to try and achieve a balance in all parts of the organisation. By simultaneously pursuing all four pathways in a particular part of the organisation, you are likely to achieve a “stuck-in-the-middle” position - and so fail to

become good at any one thing. It is a “jack of all trades” solution.

Instead, you can elect to pursue different strategic focuses and postures in different parts of the organisation if you follow a few key organisation design guidelines:

1.Recognise that one size doesnʼt fit all

Many organisations have a preference for standardising their performance management frameworks. This usually means that all management and staff operate to the same expectations and get measured in the same way.

This is clearly counter productive where we are trying to pursue different focuses in different parts of the organisation. Different parts of the organisation will have different strategic agendas - they will therefore need to be measured and managed in different ways.

Trying to achieve a common culture and way of doing things across the whole organisation is not only very difficult - it can be highly unproductive if we are pursuing different strategic objectives in different parts of the organisation.

2.Manage the organisation as a portfolio

Unless the organisation is a simple one-market, one product business, it is likely to have portfolio of businesses across several market segments. Organisations such as these should be managed like a portfolio, allowing each business in the organisation to define its business strategy in a manner most suited to the market and competition it faces.

This means that there should be a clear separation of corporate strategy at the centre (what is the shape of the portfolio and how will we fund it) from the business strategy (how will we compete in this particular business) that is developed in the business unit. Mixing the two inevitably causes confusion and represents an inherent conflict of interest - and the result is that neither strategy is well developed nor executed.

3.Ensure that the strategic agenda of a business unit matches its market

While each business unit should adopt the posture that permits it to achieve competitive advantage, this should be linked to the requirements of the market it serves.

So, a particular business unit might pursue an innovation strategy because this will give it an advantage in the market it serves. However, this is different to the case of a business unit pursuing a particular pathway because it is the preference of management - unrelated to the customers it is serving.

Differentiation in strategic style and culture that simply serves the preferences of management is likely to lead to unnecessary fragmentation of the organisation. On the other hand, differentiation linked to the needs of customers is the source of true competitive advantage.

Managing The Focus And Imbalance in The Organisation

A truly competitive organisation will allow business units to pursue pathways to competitive advantage that are related to the needs of their different markets. And they will accommodate the necessary differences in style and culture across the organisation that facilitates this diversity.

Each business unit will be focused in a different way. Each business unit will display a series of inherent trade-offs that produce the quite healthy imbalance in different parts of the organisation.

Culture is not the glue to bind disparate parts of the organisation together. A common culture is not only difficult to achieve, it can be quite unproductive in an organisation with diverse strategic challenges.

Leaders can achieve superior results by defining clearly the common purpose of the organisation and allowing the different parts of the organisation to develop the requisite style and culture to deal with the particular challenge.

About the Author

Dr Norman Chorn is a highly experienced business strategist helping organisations and individuals be resilient and adaptive for an uncertain future. Well known to many as the ‘business doctor’!

By integrating the principles of neuroscience with strategy and economics Norman achieves innovative approaches to achieve peak performance within organisations. He specialises in creating strategy for the rapidly changing and uncertain future and can help you and your organisation.

Subscribe to our regular articles, insights and thought leadership