The Drive to Improve Performance

The term “best practice” came to common usage during the benchmarking craze of the 1990s. Since then, it has been pursued by many “learning” organisations, supported by a burgeoning consulting industry who claim to have uncovered the best ways to do everything from strategic planning to systems reengineering. The promise is quite compelling: “Benefit from others’ hard-won experience and improve your chances of success”. And, argue the proponents, “...become a learning organisation along the way".

But in our view, seeking best practice solutions may not be as beneficial as they first seem. In many cases, it may kill innovation, stifle insight and understanding, and can actually destroy value in your organisation!

It Turns Out That “Best Practice” May Actually be “Past Practice”!

The primary reason is that complex organisations are very dependent and responsive to their immediate environment. And unless the practice you adopt was developed in precisely the same context as yours, it may actually be harmful to your organisation.

As outlined in our previous article (1), many modern organisations can be described as complex adaptive systems - ie they are made up of multiple connected parts (people) that have the capacity to change and learn from experience. And they also have a range of characteristics that make them inherently unpredictable and unstable under certain conditions.

What Are Complex Adaptive Systems?

A complex adaptive system (CAS) is an organisation made up of multiple connected parts (people) with high levels of interdependency between them. These parts have the capacity to learn from each other and to change in response to their environment.

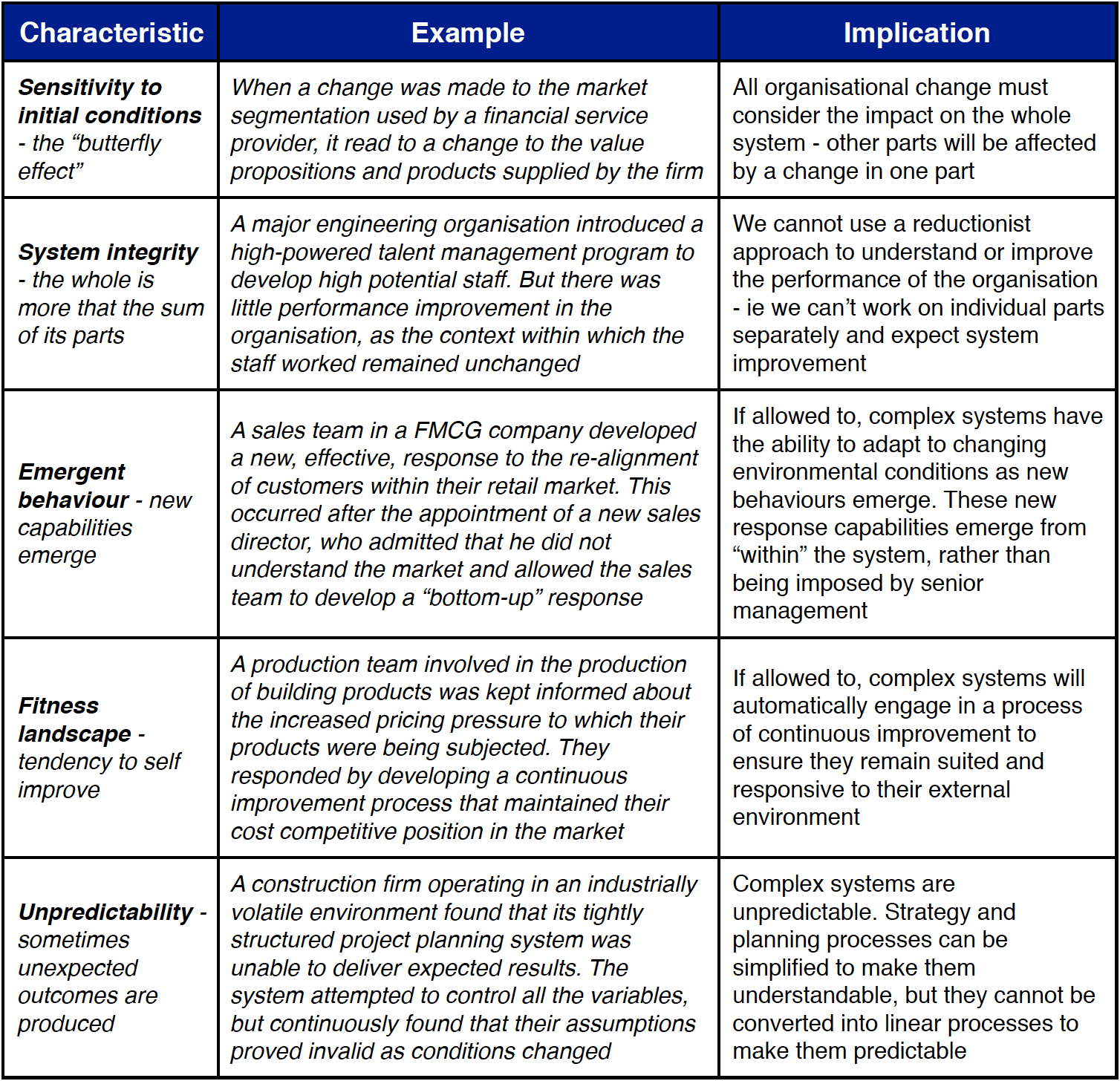

Research shows several important characteristics of complex adaptive systems as they occur in organisations (3):

This means that most organisations are capable of self management, but only if they are lead in appropriate ways (more about this later in the article).

Traditional “control-oriented” approaches can disturb their these self management and self-improvement capabilities - and actually destroy value in some cases.

So, Why Doesn’t “Best Practice” Improve Performance in Complex Systems?

Adopting “best practice” in complex systems can fail to improve organisational performance for two reasons:

- The process of benchmarking and “best practice” relies on the traditional scientific method of observe → hypothesise → predict → experiment: We observe a successful practice in one organisation and then seek to implement it in another in the hope that we can replicate this good performance. But this is based on the assumption of repetitive events. And the notion of complexity invalidates repetition and prediction!

- “Best practice” is a reductionist technique that imports an individual process (or structure) and implants it into a new system without necessarily considering the context of this new system: Reductionist approaches attempt to explain complex systems in terms of the laws of physics and chemistry by reducing the complexity to simple terms. It often leads to the assumption that we can directly control human behaviour. This, in turn, leads to a range of dehumanising processes and often, a significant alienation of people.

Put another way, analytical thinking, which takes things apart, fails to recognise that the system is more than the sum of its parts. We need to see the whole system and recognise that the thing we wish to understand is part of a larger system. This calls for synthesis thinking, rather than analytical thinking. Synthesis is another way of looking at the world and recognises the importance of the whole system - the system integrity.

How Can we Improve Performance in Complex Organisations?

Based on an understanding of complex adaptive systems and the use of synthesis thinking, we can identify five approaches to improve the performance of complex organisations:

1. Address complexity with complexity:

Ensure that the system has at least the same amount of complexity as the environment. The law of requisite variety reveals that we cannot expect a simple solution / organisation to cope with a complex situation. So, avoid looking for simple, quick fixes to complex problems.

2. Use a diverse range of models and approaches:

Using a diverse range of approaches or models improves the probability of success in an complex organisation or environment. For example, the use of scenario planning (which considers a range of alternative futures) is more likely to improve future performance than a conventional strategic plan (which attempts to predict what will happen).

3. Recognise the dependence on context:

“Best practice” is most often past practice - because the context in your organisation will almost always be different. Ensure that you understand the context and design a solution that maintains the overall system integrity.

4. Assume subjectivity and co-evolution:

Your plans will almost always be reinterpreted and refined by those in the organisation as they address the challenges of the environment. Expect this and regard it as feedback that can improve the whole system. Don’t insist on “rolling out” your strategy and expecting everyone to stick to the script.

5. Assist your people to make sense of the world:

The role of the leader is to help make sense of the world, promoting insight and understanding. Your role is to help your people understand the challenges they face, rather than telling them how to solve them. By working in this way, you will allow your people the “elbow room” necessary to promote real performance improvement.

References

(1) Talent Management is Dead - killed by complexity

(2) Can there be a Unified Theory of Complex Adaptive Systems?, John Holland, 1995

(3) Maurice Yolles, Organisations as Complex Systems, 2006, USA

About the Author

Dr Norman Chorn is a highly experienced business strategist helping organisations and individuals be resilient and adaptive for an uncertain future. Well known to many as the ‘business doctor’!

By integrating the principles of neuroscience with strategy and economics Norman achieves innovative approaches to achieve peak performance within organisations. He specialises in creating strategy for the rapidly changing and uncertain future and can help you and your organisation.

Subscribe to our regular articles, insights and thought leadership