The 'Brain New World'?

The ‘Brain New World’ is an attempt to understand the changes taking place in our organisations and the way we navigate through these unprecedented conditions of complexity and uncertainty. By using the human brain as an analogy, we explore aspects of the modern organisation and the way we approach strategy.

We see several things we can learn about organisations by recognising that an organisation not only

has a brain, but in many respects, it

is

a brain.

Why is This Relevant Now?

Current conditions have placed our organisations at the confluence of four major forces:

The confluence of these forces has produced unparalleled complexity in our environments. With complexity comes greater uncertainty and risk. Furthermore, we know that complex systems are characterised by a number of significant features:

The butterfly effect:

You intervene at one point in the system, and something happens at another

System integrity:

The whole system is more than the some of its parts. In fact, the whole is also different to the sum of its parts

Unpredictable, emergent behaviour:

Because of the inherent unpredictability of complex systems, events and changes cannot be accurately planned. Instead, they emerge over time as the system develops its own dynamic

Brittleness:

As complex systems grow and connectivity increases, there is a tendency towards increased centralisation. This creates a brittleness in the system that can result in increased momentum (negative or positive) in the system and cause it to break down.

Importantly, organisations are impacted in the same way. Because most modern organisations are highly connected and made up of many interdependent parts, they too can be characterised as complex adaptive systems. And they too are subject to the same features of the bitterly effect, systems integrity, emergent behaviour and brittleness.

How Does This Impact Competitive Advantage?

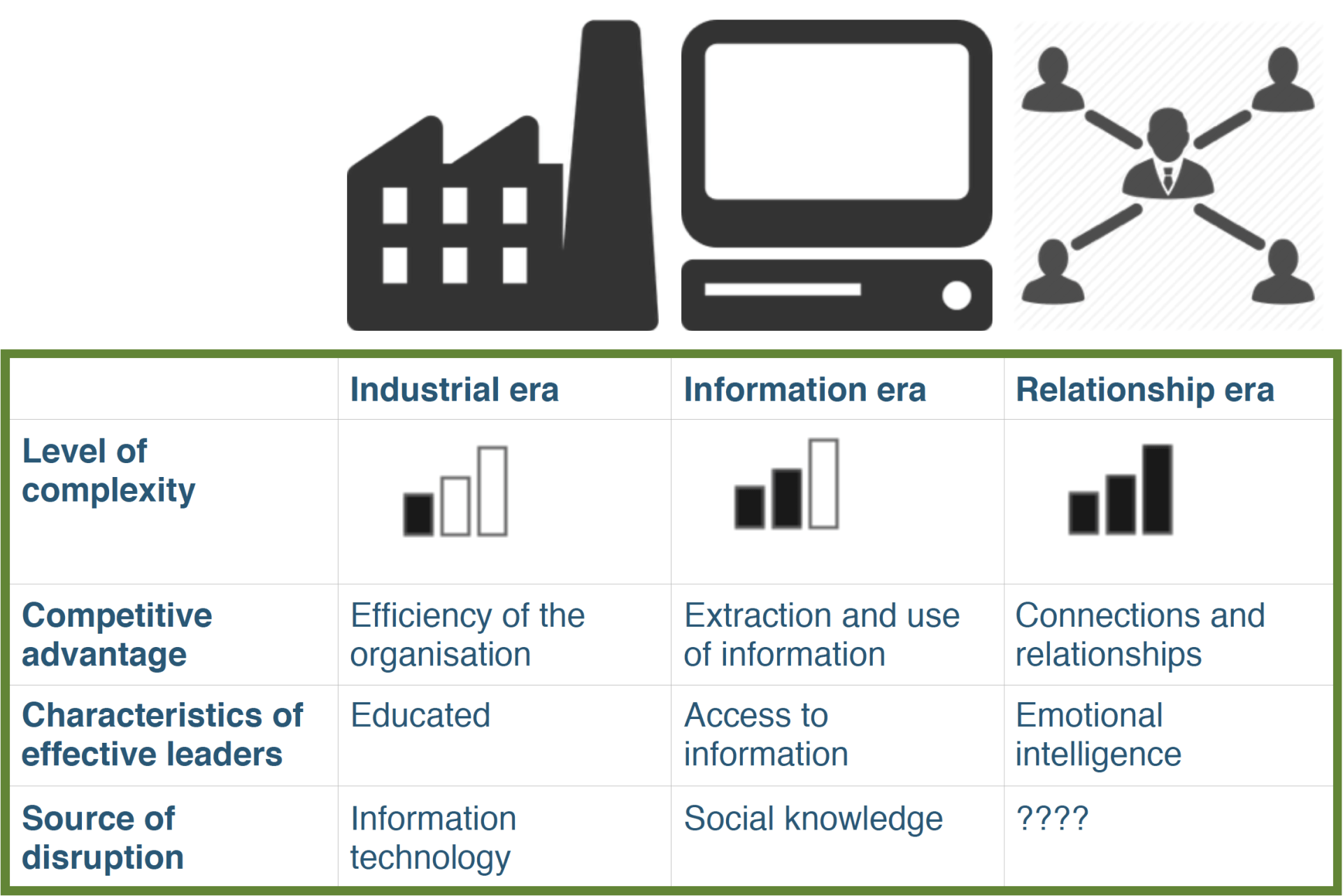

Some believe that the concept of competitive advantage is not applicable to all organisations, particularly those involved in not-for-profit or public sector activities. However, the broader meaning of competitive advantage is that it measures the extent to which an organisation represents the most effective and efficient use of its resources - whatever its purpose or ownership.

In this sense, it is a useful way to measure the effectiveness of an organisation’s strategy. So how has the concept of competitive advantage evolved in response to increased levels of complexity? Or put another way, how has the purpose of strategy evolved in this time?

Table 1 below shows how this evolves as economies move from the industrial era to the information era - and more recently, to the relationship era. In each case, the form of competitive advantage - and therefore the strategy - evolves in order for the organisation to be effective. And the levels of complexity rise accordingly.

As a consequence, we are witnessing real changes in the nature and form of organisations. Organisations are developing the capabilities to execute on strategies based not only on efficiency, but the ability to use information and form authentic relationships and connections as well.

It is these changes that has prompted us to search for new metaphors to describe organisations. While the ‘machine’ metaphor has been a useful way to define organisations based on efficiency, we need another analogy to portray more complex organisations that focus on connections and the effective use of information.

Table 1 - The evolution of strategy and competitive advantage

What is the Brain New World?

The ‘Brain New World’ is the use of the human brain as an analogy to describe and explore modern organisations and their strategy.

The brain is a highly connected network and displays many of the characteristics of a complex adaptive system described earlier:

The butterfly effect

The brain is a system of highly connected and interdependent parts - changes in one part of the brain impact on other parts.

Systems integrity

The brain is more than the sum of its parts - it has an overarching purpose or function in humans.

Unpredictable, emergent behaviour

The brain learns and makes connections in an unpredictable manner - the process of creative insight occurs when information is connected in new and different ways.

Brittleness

Where a small number of neurons (the brain’s building blocks) become too highly connected and resemble ‘hubs’, they overwhelm the brain’s networks and cause system breakdown. This is the nature of an epileptic seizure.

Using this analogy, we can examine an organisation by using our knowledge of the human brain.

The Integrated Brain

Based on extensive research in neuroscience, we have learned that the human brain operates as an integrated whole and has an overarching purpose or goal.

More recently named the “1:2:4” model of the brain, this offers a number of powerful insights into the nature of organisations and their strategy (1).

Key findings on the brain

Applying the findings to organisations

The brain is an

integrated whole

As complex systems, organisations are integrated wholes. They cannot be changed or improved by breaking them down into their constituent parts. This ‘reductionist’ approach is a key hangover

from the machine analogy and ignores the fact that changes in one part of the system will impact on other parts. Organisations need to be viewed as a whole - from a systems perspective - in order to understand how they operate and respond to change.

It’s key role is to

seek safety

The underlying principle of ‘organisation’ is to eliminate uncertainty. Uncertainty and change represent danger. Organisations will, therefore, naturally resist change - particularly if they are predicated by the use of ‘burning platform’ (threat) messages

Non-conscious

processing of external

cues occupy most of

the brain’s functioning

This underlines the importance of hidden assumptions and distorted

perceptions that are shaped by the organisation’s prevailing culture.

External cues are understood and interpreted within the frame of

reference provided by the culture - and this generally occurs at a

non-conscious level. In most cases, organisations are not aware of

how their understanding and responses are predetermined by the

culture

These external cues

manifest in a tangible

reaction

The key to effectiveness is to process and analyse the external

cues to understand their cause, before ‘knee-jerk’ reactions. While

this is often very difficult, pausing and thinking before action enable

organisations to develop new insights into the real meaning of the

external cues. But this requires a strong commitment to the ‘pause’

- and is one of the key characteristics of good strategic thinking

The brain seeks to align

and regulate any

resultant decisions and

actions

The self regulation processes in organisations - such as

performance management and governance - play an important role

in ensuring integrity and alignment with values. However, they come

under significant pressure when the organisation experiences

negative (losses) or positive (significant success) external cues.

What are the Insights For Organisations?

Five key insights are presented below:

1. Limit the use of a reductionist approach to understand and manage organisations:

Breaking the organisation down into parts (eg sales, finance, operations) and then working on them individually will often fail to improve the organisation. It may even result in a deterioration of overall performance.

This is an approach typified by the ‘best practice’ movement whereby we seek to import a particular practice (eg a sales management technique) from one system and then embed it into another organisation. This assumes that the various parts of the organisation are not highly connected and that they can be modified without causing a reaction (usually unintended) in another part.

2. Recognise that it’s natural for an organisation to resist change:

Organisations are designed to eliminate uncertainty and change. Lead the change process by stressing the positive aspects - ‘towards messaging’ - and giving people an opportunity to understand and experience the benefits. Wherever possible, avoid the use of ‘burning platform’ messages that create a sense of danger and promote emotional responses that generally eliminate engagement and creativity.

Try to ‘build a bridge’ for people to understand how they will move from their current position to a future position. Many middle and junior staff lack the frames of reference and future orientation to understand a very different future - it simply makes no sense to them because they cannot conceive of how it will work.

3. Understand the powerful impact of the non-conscious aspects of culture:

The impact of culture on organisations is hardly a new insight. But we are learning that this is far more pervasive than initially understood. Because so much of the processing of these external cues occurs non-consciously, the organisation is largely unaware of its effect.

It shapes the choice of performance measures, how data is analysed and interpreted, what leadership behaviours are valued, and even the types of planning tools that are used. These factors will determine the repertoire of behaviours and strategies used by the organisation - mostly without a conscious awareness.

4. Appreciate the value of a ‘pause’ before responding to external cues:

Most organisations experience a need to respond quickly to an external cue, whether negative or positive. This need to be ‘action-oriented’ often drives out opportunities for reflection and the generation of new insights.

The drive for action - often disguised as a sense of urgency and ‘real time management’ - is the enemy of good strategic thinking. But there is usually a window of opportunity between stimulus and response - a chance to examine, analyse and re-think the true meaning of the external cue.The real value of this ‘pause’ is that it allows for an opportunity to combine and recombine the information available.

Often this results in new insights and understanding about the external cues - and opens up different avenues and options for action. We’re not advocating procrastination or ponderous decision making. Simply recognise that action can drive out thinking and the possibility of new insights - and leave the repertoire of behaviours and strategies unchanged. And this can be disastrous in a complex and changing environment.

5. Protect the governance processes - the self regulation functions - particularly during periods of negative or positive momentum in the organisational system:

The ability to self regulate is at its most vulnerable when the organisation is under pressure from negative or positive cues. When things are going badly for an organisation, it may be tempted to take short cuts, or to make short term decisions. Under pressure from a threat or perceived danger, the organisation often loses access to its logical and creative capabilities.

Similarly, when experiencing a series of positive outcomes (success), the same pressure exists to override the self regulatory systems that created the success in the first place. The sense of euphoria and ‘self belief’ is often so powerful that the organisation can develop an unrealistic sense of omnipotence.

Becoming A Brain New Organisation

We have a long way to go before we can claim we understand the new model of organisations in this complex world. The five principles above represent a start to building the type of capability needed by organisations as they seek to thrive in this brave new world.

References

(1) See an outline of Gordon’s “1:2:4” model in the Appendix

About the Author

Dr Norman Chorn is a highly experienced business strategist helping organisations and individuals be resilient and adaptive for an uncertain future. Well known to many as the ‘business doctor’!

By integrating the principles of neuroscience with strategy and economics Norman achieves innovative approaches to achieve peak performance within organisations. He specialises in creating strategy for the rapidly changing and uncertain future and can help you and your organisation.

Appendix

Key findings on the brain

Implications for humans

The brain is an integrated whole

Rather than function as a collection of different parts that manage different functions, the brain is a highly interdependent system. Changes in one area impact on others, and the brain learn to compensate for deficiencies in one part of the system by developing ‘workaround’ strategies

It’s key role is to seek safety

The brain’s threat circuitry is greater than the reward circuitry. It is biased towards the elimination of threat over seeking reward. Furthermore, the brain’s rational and creative capabilities are severely curtailed in the face of danger, including the threat of social rejection

Non-conscious processing of external cues occupy most of the brain’s functioning

The brain has most (in excess of 99%) of its processing capacity dedicated to the non-conscious processing of external cues. In most cases, this processing occurs outside of your conscious awareness - but will affect the manner in which you respond and act

These external cues manifest in a tangible reaction

Once these external cues have been processed, you become aware of them by way of some physical reaction in your body, e.g. sweaty palms, increased heart rate or a feeling in your gut

These reactions are then processed and analysed

After becoming aware of these physical sensations, you begin processing and analysing these reactions - you think about their cause and what it means to you. This gives rise to a decision or action. However, you may not take the necessary time to ‘think’ about this before making a decision or acting

The brain seeks to align and regulate any resultant decisions and actions

The brain has a self regulation function which is designed to ensure that your decision and decisions are well considered and aligned. This may be less effective when you are tired or otherwise impaired.

Subscribe to our regular articles, insights and thought leadership