Given that uncertainty and risk present a threat to us as leaders, how do we move past the tendency to simply ignore it and hope it will go away?

I’m not suggesting that we have a tendency to consciously ignore risk, but the practice of running a “risk register” is sometimes like parking the risks in a ledger and then just getting on with our business.

Part of working out how to integrate risk into your leadership is to understand how it affects us. This will then identify some ways in which we can integrate it into our leadership practices.

What is the biology of risk?

The ‘biology of risk’ refers to the way our brain and body reacts to risk and uncertainty.

Much of the risk we encounter is due to the inherent uncertainty in the environment. This uncertainty — and the risk of things going wrong — has a significant effect on us. In essence, it is registered as danger by our brain and our body.

Because a primary goal of our brain is to protect us from danger, this uncertainty induces stress at both a conscious and non-conscious level.

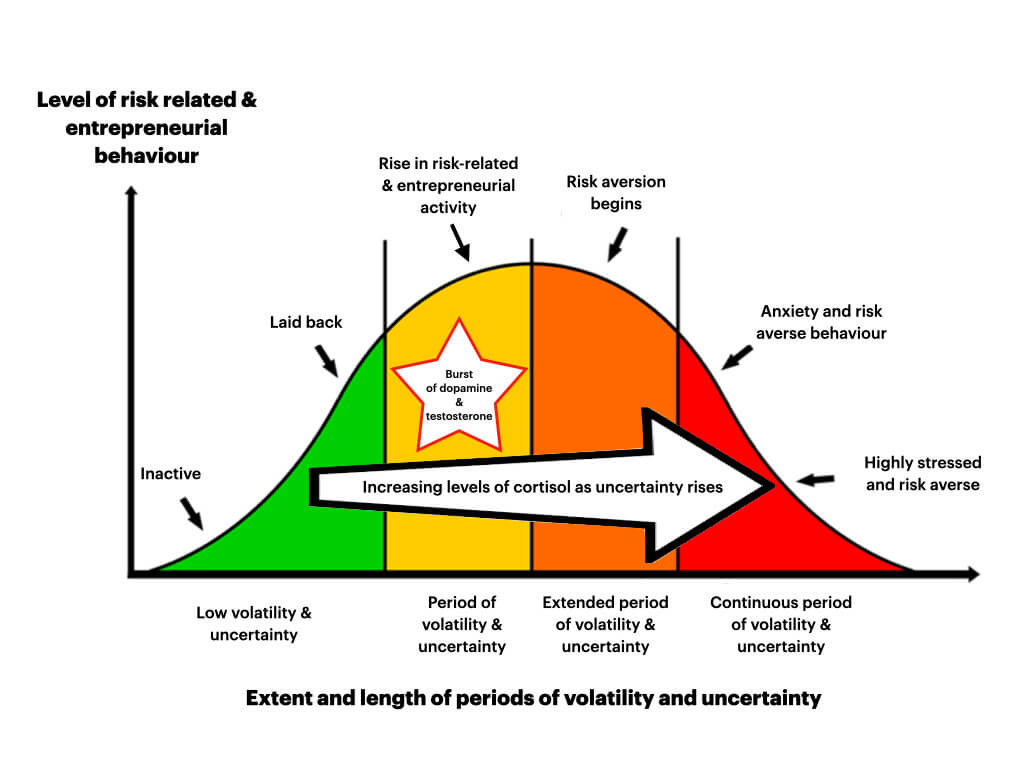

Not all forms of stress are bad. Indeed, some forms of stress are enjoyable and quite productive. In moderate amounts, we get a rush from stress and thrive on risk taking. For example, when we see an opportunity that results from some volatility in our environment, our body produces a powerful cocktail of dopamine and testosterone. This allows us to expand our risk taking and engage in innovative and entrepreneurial activity to capitalise on the opportunity.

This type of stress has been termed the “challenger” response. As you can see, this is a productive and important use of stress to allow us to advance and improve our situation.

However, if this volatility and resultant uncertainty continue for a long while, our sense of danger grows as we realise that we no longer understand what is going on. This sense of danger produces an increase in the production of cortisol (the body’s natural response to danger) which then acts to curtail our risk taking and entrepreneurial behaviour.

This reaction may be unfortunate since long periods of volatility and uncertainty are exactly the times when leaders need to be bold and decisive.

The response to volatility and uncertainty suggests that a leader’s risk appetite is not stable, but rather that it shifts according to the amount of uncertainty and threat in the environment.

Short bursts of volatility register as novelty and encourage more risk taking behaviour. Continued and erratic volatility induces a rise in cortisol and produces risk aversion.

How does the biology of risk affect leaders’ risk appetite?

An important implication of the biology of risk is that we are likely to see swings in leaders’ appetites for risk in their strategy. Higher risk entrepreneurial behaviour is evident during short bursts of volatility, while risk aversion manifests in continued volatility and uncertainty.

Furthermore, we know that the anticipation of erratic and volatile conditions also evokes a strong stress response. Sometimes it is more stressful not knowing when or if something bad will happen, than if it actually happens. This too can lead to strong risk aversion.

As mentioned above, this reduction in higher risk entrepreneurial activity may not be in the best interests of a business during extended periods of uncertainty.

Given this variability in risk appetite, what are the lessons for leaders as they seek to encourage appropriate entrepreneurial (risk taking) behaviour in their organisations?

Managing the biology of risk to promote entrepreneurial behaviour

Based on the evidence above, there are three things leaders can address:

1. Be conscious of the effect of uncertainty on your own risk appetite

Recognise that long periods of uncertainty may inhibit your risk appetite and will reduce your entrepreneurial instincts as a result of the rise in cortisol levels. This may not be in the best interests of your organisation, as long periods of uncertainty may well benefit from more innovative behaviour during this time.

2. Avoid continuous volatility and uncertainty within the organisation

While we may need ongoing adaptation to meet the challenges of the market, “keeping your people guessing” about when you will make the next change is not likely to result in productive and adaptive behaviour.

People will be anticipating the next change and will be in a state of hyper-vigilance. The continued uncertainty and stress will raise cortisol levels, increase risk aversion and reduce the much-needed entrepreneurial behaviour.

3. Introduce planned volatility and novelty through a program of Agile Sprints and / or Scenario Planning

Agile Sprints will give people an opportunity to work in a novel and exciting way on a specific project. The short-term uncertainty provides an opportunity for people to work in a way that allows them to give expression to higher-risk entrepreneurial behaviour for a defined period of time.

Scenario Planning creates a forum in which people can explore different futures in a novel way. The opportunity for creative and divergent thinking — and the interactive processes — elicit higher levels of dopamine (fun) and testosterone (energy) and are likely to produce more entrepreneurial behaviour.

By understanding the biology of risk, we understand that leaders display variations in their risk profile, depending on the context. It is possible to manage this context — the level and duration of volatility in the organisation — in order to enable a more appropriate risk appetite.

Successful leaders are able to manage this context (the level of volatility in their organisation) to encourage appropriate levels of entrepreneurial behaviour to suit the circumstances.

About Norman

Dr Norman Chorn is a highly experienced business strategist helping leaders build highly successful and resilient organisations. Well known to many as the ‘business doctor’! By integrating the principles of neuroscience with strategy and economics Norman achieves innovative approaches to achieve peak performance within organisations.

Subscribe to our regular articles, insights and thought leadership