WHY SHARED SERVICES DON’T DELIVER

In the horns of a dilemma

“We want multiple value propositions for the different market segments we serve, but also need to reduce our costs by eliminating duplication of services”. This is a typical conversation I’ve been having with clients since my recent newsletter on strategies for winning and keeping customers. They acknowledge the need to have a series of different value propositions and customer experiences for the different market segments they serve, but they are also keen to remain cost-competitive. And so the conversation turns to the creation of shared service facilities inside their organisation.... What’s the problem here? Surely, the creation of a shared service capability, such as HR, IT or Finance, allows us to achieve economies of scale by sharing expensive resources (people, office space, computers etc) and standardising processes through the organisation?

Well sadly, there is little evidence to suggest that the total costs of the service provision are reduced*. Yes, there are efficiency gains in the costs of many of the individual activities, but the overall costs of the exercise are usually higher due to what has become known as failure demand. Failure demand is the additional demand that arises from the organisation’s inability to meet the customers’ needs properly the first time, and the rework required to fix the problem caused. And that doesn’t take into account the customer dissatisfaction and possible defection to another supplier.

I’ve seen this problem in many organisations. They want to save costs by eliminating (what they see as) duplicated costs across different parts of the business. And so they create a shared service capability which aims to share expensive resources and standardise processes across the organisation. In this way they aim to achieve greater efficiencies and cost savings through economies of scale. But the “internal” customers, who are essentially captive to these services, are increasingly dissatisfied and have to make other arrangements to work around the service deficiencies.

This often includes hiring contractors for “special projects” to supplement these services, or simply suffering the inefficiencies of poor service levels. And the “external” (real) customers? They simply have to keep coming back and trying to get their needs met and problems solved. All at a high cost - both in resources and lost customer franchise. This is the nature of failure demand. Why are economies of scale not producing efficiencies? What’s the real cause of this problem? Well, it seems as if there are several causes that relate both to the nature of the work and the way it is organised:

1. Economy of scale has only a limited impact on people working in a knowledge based service organisation

The research shows that knowledge-based workers involved in service delivery are not motivated by the same criteria as piece workers in a manufacturing operation. So, getting them to work more quickly or efficiently by organising them into a “production line” is usually counter-productive. And, as we centralise the services to save on duplication, we increase the complexity of the processes geometrically by way of the need for handovers and integration. This causes the increase in failure demand, and a resultant increase in total costs to the organisation. The economy of scale hypothesis is based on a manufacturing context where the key challenge is to produce outputs at the rate of customer demand. In service provision, the challenge is to design a system that absorbs the customers’ demand for variety.

2. Standardised services only rarely meet the needs of different customer requirements

In a service environment, the “product” is only created at the point of interface with the customer - ie in the interaction between the customer and service provider. This is unlike the manufacturing scenario, where the product is made centrally and then shipped out to the customer. Because each customer interaction is relatively unique (customers are all slightly different), the service product has to be created slightly differently each time. It is this ability of the organisation to absorb the customers’ demands for variety that actually reduces the total cost to the organisation. The reduction in total cost due to the reduction in failure demand may, at first, seem counter-intuitive. After all, we seem to be suggesting that allowing for variation actually reduces the total cost to the organisation! But, the standardisation of services increases the number of handovers in the process - and this increases the degree of fragmentation in the provision of the overall service. This increased complexity inevitably results in more errors and rework - with a resultant increase in demand failure. So, the standardised service is certainly busier with a greater volume of throughput - but much of it is rework and duplication to correct the errors made by not meeting the customers’ precise needs.

So, what does produce efficiencies?

It is ironic that so much of the thinking on efficiency within a service organisation is based on “lean thinking”, but often overlooks the fact that a key driver in this approach is the elimination of waste. And waste is eliminated by, amongst other things, improving the flow through the process. So, it is not the volume of transactions that produce the savings, but the elimination of waste through improved flow. In this context, economy of flow means that:

✓ the process matches the requirements of the customer and is able to absorb the customers’ demand for variety

✓ the number of handovers and resultant integration is reduced so as to limit the overall complexity in the system

✓ the failure demand (requirement for rework and duplication) is reduced to lower the total cost to the organisation.

How can this be achieved?

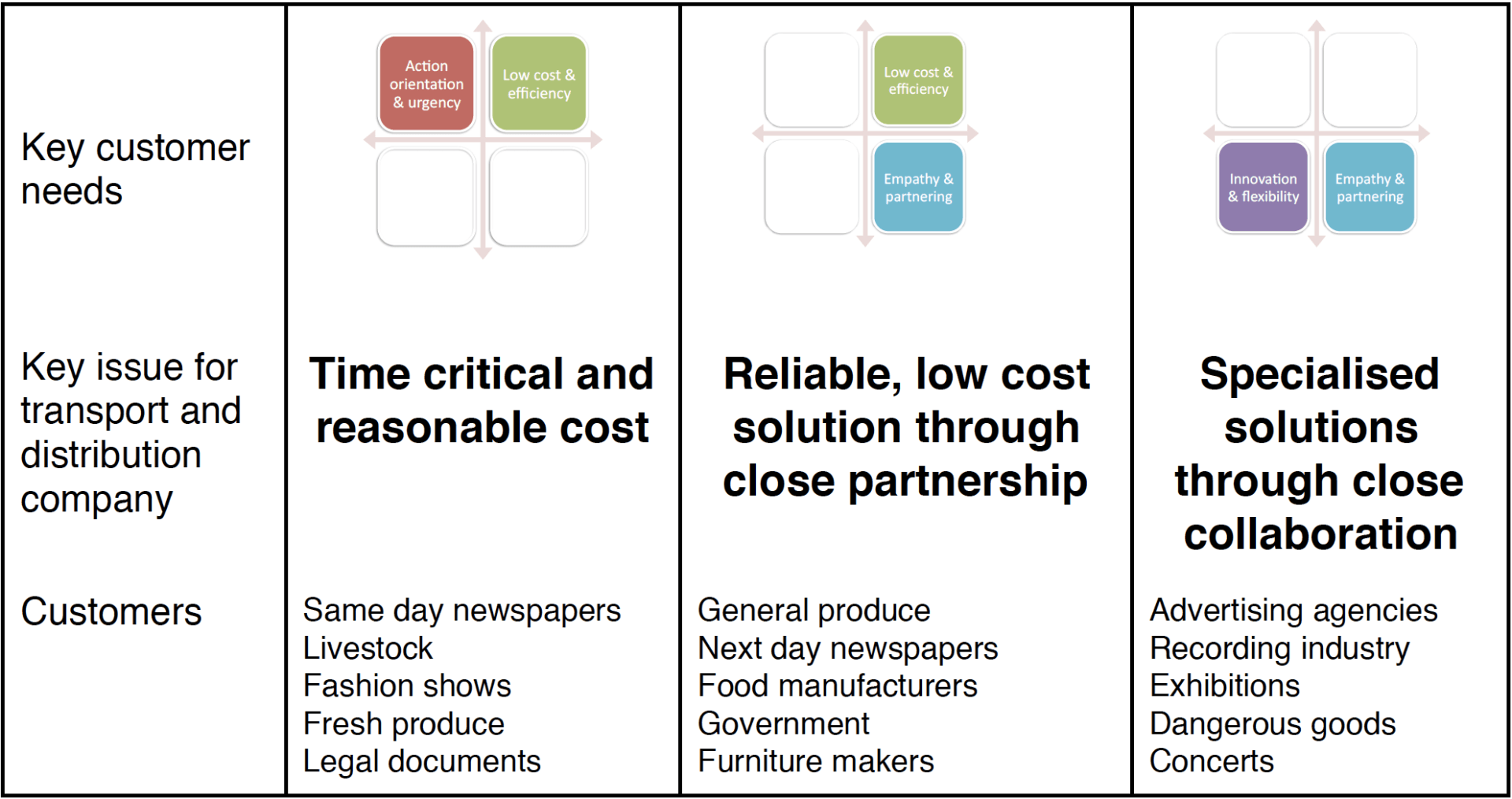

If the goal is to improve customer focus and to improve the efficiency of the system, how can this be achieved in an organisation? Returning to the opening quote of this newsletter, this was a conversation with a client some while ago. The organisation is a major transport and distribution company who faced a multitude of clients across the market. In my previous newsletter, we described how we segmented the market for this company so as to allow for economy of flow within each of the newly defined segments - see the table below: By defining the business of the company around the three key market segments, we were able to produce economies of flow within each segment. This meant that the company was able to set up three “business units” - one to deal with each of the market segments. While this approach required some duplication of resource to enable a series of different customer interfaces, the reduction of waste (total cost) across the whole business was substantial!

The organisation design - and the recognition that efficiencies would be produced by allowing economy of flow - mean that each business unit was able to more readily absorb the demand for customer variety. Indeed, they were set up for that very purpose. Consequently, the failure demand reduced dramatically and the company was able to achieve high customer focus and a reduction in operating costs.

This solution obviously requires a different approach to the way that the organisation is designed and built. This is the subject of my next newsletter and the workshop I am running in Sydney on 5th September, 2011 (see the information and registration link below).

How can we achieve customer focus and cost reductions?

While there are no silver bullets to resolve this problem, there are a few key pointers that should be borne in mind:

• Economies of scale

- increasing the sheer volume through a process - will not necessarily produce efficiencies in a knowledge-based service organisation

• Standardising of services

- Standardising of services will often produce an increase in failure demand and total cost - because of the inability of the system to absorb the variety in customers’ demands

• Efficiencies

- Efficiencies and cost reductions are more likely to result from economies of flow in the system. This is an outcome of better market segmentation, business definition and organisation design.

Subscribe to our regular articles, insights and thought leadership