What's the big deal?

Current conditions are pretty challenging for leaders. Complex environments and high uncertainty make decision making difficult and risky.

There are few simple solutions - and decisions seem to have multiple options and consequences. So how do we manage through this?

Many would argue that we have to be more “strategic” in our approach. Job advertisements and role descriptions describe the ideal candidate in these environments as being strong “strategic thinkers”. What does this really mean and how can we develop that ability?

So, what is strategic thinking?

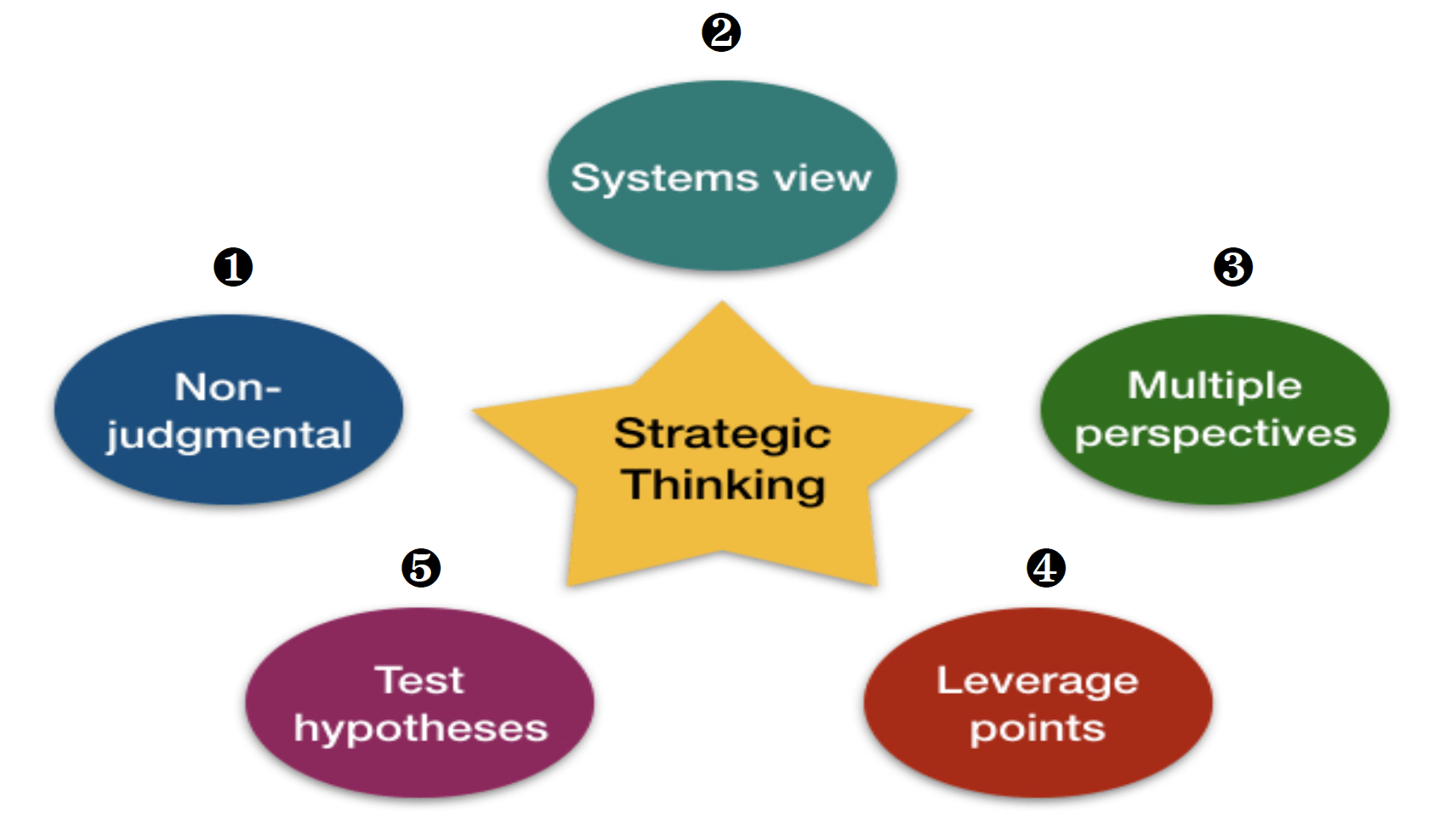

One way to understand strategic thinking is to recognise it as the way you focus your attention and energy in a given situation.

I’ve identified five key elements:

1. Non judgemental

This may seem obvious, but a critical part of strategic thinking is to view a situation in a non-judgemental way, without bias or preference. While obvious, it is not that easy to implement, We shall refer later to the critical skill of ‘mindfulness’ that is so central to being non-judgemental.

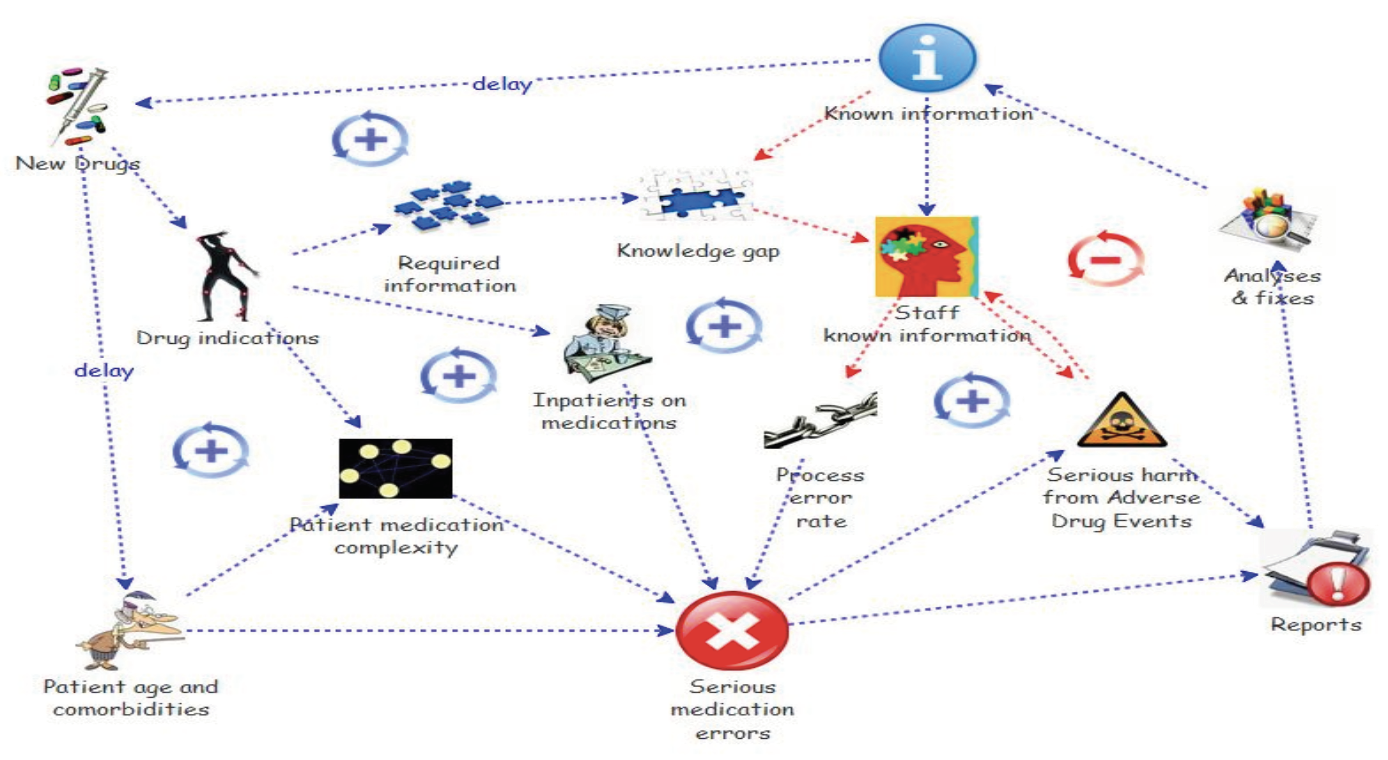

2. Systems view

In essence, this means that the situation should be explained in terms of all the key elements to which it is related. This is usually best done graphically by mapping the key relationships between the elements, and explaining the linkages. The diagram below is an example of this mapping for the release of a new pharmaceutical drug:

3. Multiple perspectives

Good strategic thinking will look at the situation from multiple perspectives - ie view the situation from the position of each player in the situation.

This provides an understanding of the different motivations of the players and how their needs may be satisfied. This is critical to the next element - the key leverage points.

4. Leverage points

Most situations have one or more leverage points - those factors that can unlock the problem and provide a possible solution to the situation.

By understanding the perspectives and needs of the different players, the leverage points that point to a solution may be identified.

5. Test hypotheses

As you assess the situation from a systems perspective, a range of possible solutions or theories can be identified. These should be treated as hypotheses - possible solutions to be further assessed.

Each hypothesis is then tested to identify one that produces the optimum outcome.

What Drives Strategic Thinking?

A key to improved strategic thinking hinges around the ability to appropriately focus your attention and energy at crucial moments. This is about ‘mindfulness’ and the creation of specific mental pathways to understand and make sense of these situations.

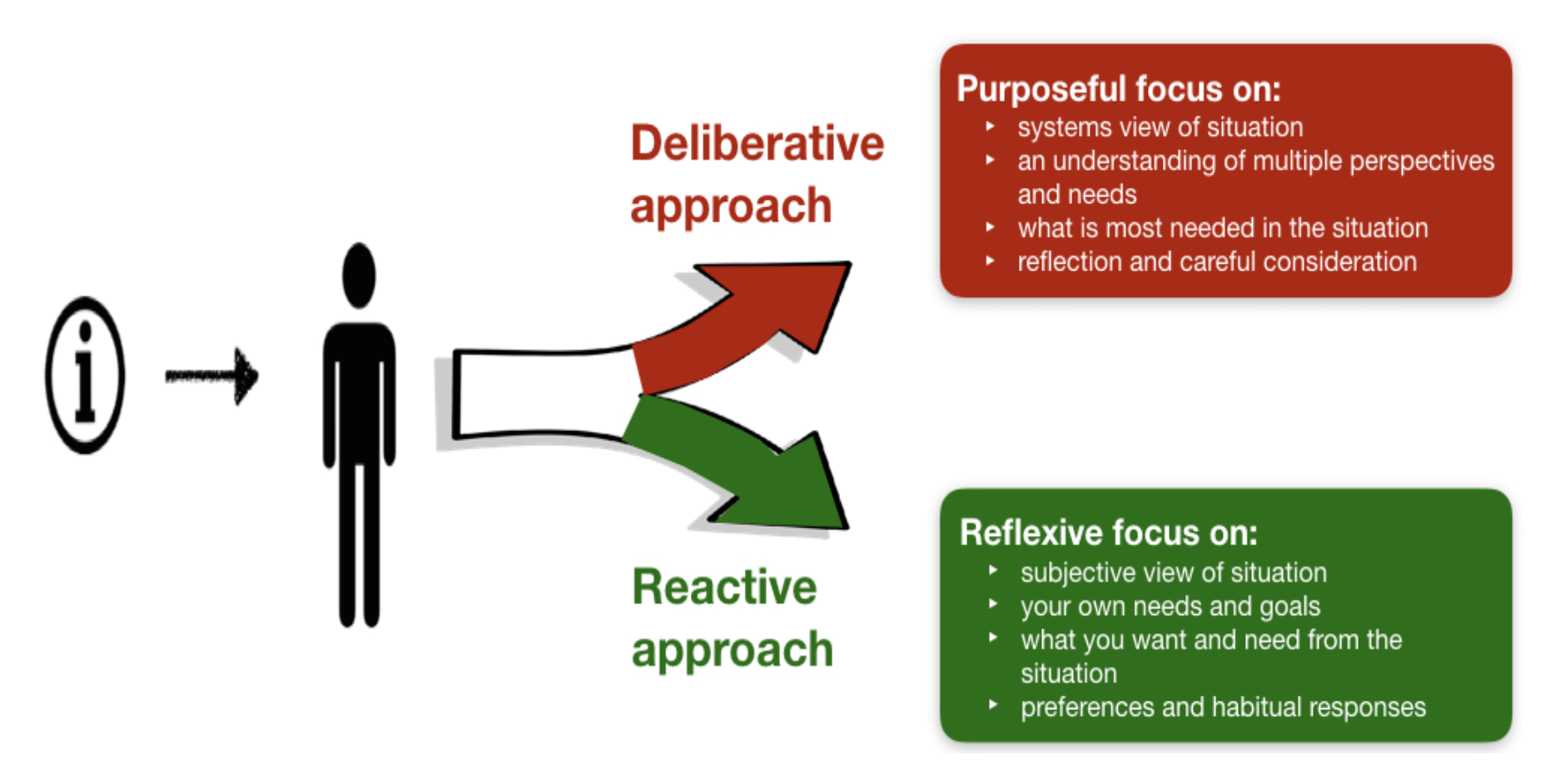

In simple terms, there are two ways in which we perceive and make sense of a given problem or situation:

The Reactive Approach - a tactical focus

This is the fast, almost instinctive approach that we often bring to problem solving. It relies on previously used solutions and preferences, and is focused on producing the best outcome for you and your needs.

It is also described as the narrative approach, because it relies on your values and your “story” about who you are and what you want. Since it relies on instinctive pattern recognition to formulate a solution, it can be quite deceptive and miss important information. However, we use this approach often as it requires less mental effort and resource.

The Deliberative Approach - a strategic focus

This is a purposeful, more time consuming approach that requires some mental effort and consideration. It adopts a non-judgemental systems view of the situation and considers what is most needed (as opposed to what you want).

It is also termed the direct network approach and follows a different mental pathway to the Reactive Approach. Mindfulness is a critical requirement here, because of the requirement to consciously focus attention and energy on a systems view of the situation. It also reduces the effect of personal preferences and needs on our perspective.

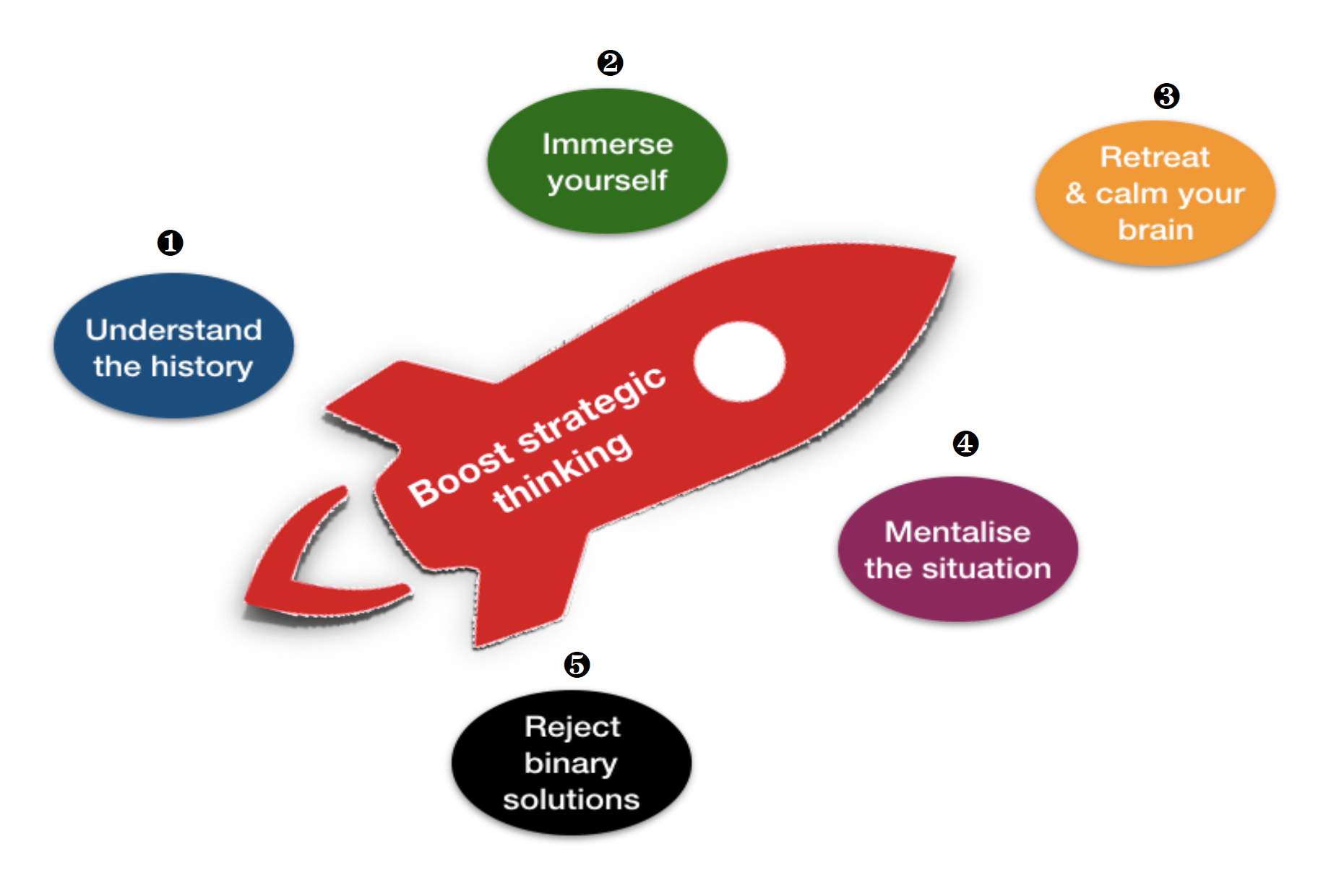

How Can I Boost My Strategic Thinking?

I outline five key actions to help in boosting your strategic thinking:

1. Understand the history

The appropriate starting point is to study the history of these or similar situations. In essence, this means doing any research you can in order to understand how these situations occurred in the past, how they were resolved, and the latest thinking / theory on how to deal with these issues.

This provides a few reference points and possible hypotheses that can be tested later.

2. Immerse yourself

Strategic thinking is not an armchair exercise - at least not in the early stages. You need to gather as much first-hand information as possible about the situation and the key players in the system.

By immersing yourself in the situation, you provide your brain with important non-conscious cues that are called upon later when analysing the situation and generating new insights. But importantly - you should consciously ‘forget’ all that you learned during the study of the history and theory.

Some call this developing a ‘beginners mind’ - where you observe and listen to your first-hand information in a naive and non-judgemental way. Avoid jumping to conclusions at this point - your role is to observe and be aware of all that you see, hear and feel. (This can be difficult to master).

3. Retreat and ‘calm’ your brain

Now you need to move out of the phase of intense concentration and focus - and into a period of reflective insight. This means removing yourself from the immediate situation and blocking the flow of visual and auditory information related to the problem.

This ‘retreat’ will allow your brain to mull and non-consciously group and re-group all the information gathered to date. As the term implies, ‘insight’ comes from inside. It is the work performed by your brain while you are not consciously focused on the problem or situation at hand.

There is much research and evidence of this non-conscious insight process - as well as its ability to generate new and creative perspectives on the the problem. There are also specific actions you can take to calm your brain and increase the likelihood of a better solution. They include:

- focus on the immediate task at hand, rather than any possible outcomes

- chunk the information into fewer pieces or categories - this makes it easier to manage

- reframe the problem as a challenge, instead of possible ‘life or death’ consequences

- name and label the concerns you have about the situation - this reduces the sense of overwhelm

- concentrate on the controllable factors, rather than those that are uncontrollable

- try to remain positive in the situation by remembering previous successes in this space

4. Mentalise the situation

Mentalising is the term to describe the objective, systems-thinking approach adopted by good strategic thinkers. It involves:

- looking at the situation as a system and identifying the key players and their interdependencies - view them as characters in a movie or novel

- asking yourself about their motives and intentions - and what they are likely to do to pursue these

- identifying the leverage points in the system - what would it take to move or change the position of one these players?

- thinking about the what needs to be done and what creates the best long term value

- removing your preferences (and those of people around you) from the situation - and trying to view the situation dispassionately

5. Reject binary solutions

Binary solutions are often the product of reactive thinking - they involve the usual ‘win-lose’, or ‘only two-options’ solution.

Reject these solutions, particularly in complex situations and problems. Force yourself to generate as many alternatives as possible. This increases the chances of generating a creative insight that breaks the logjam in the situation.

Practice Makes Perfect

Neuroscientist Daniel Hebb explained thought processes in terms of the connections between the neuron assemblies (nerves) in the brain (3).

His research, now key to our understanding of cognitive processes, identified that mental pathways that are continuously used will become physically associated with one another in the future. In other words, the more we use a particular pathway, the easier it becomes to follow that pathway in the future. The pathway can become totally automatic.

The implication is clear. The more we practice the Deliberative Approach and Mentalising process, the more likely we are to use that approach in the future. And the better our strategic thinking will become.

To be clear, the approach is not easy at the outset - particularly if we have tended to rely on a more Reactive and ‘gut feel’ approach in the past. It will take mental effort and discipline.

But the rewards - better strategic thinking - are likely to be valuable to you in the future.

What is strategic thinking? How do we do it really? What does this really mean and how can we develop that ability?

References

1) Mindfulness and the Quality of Organisational Attention, K Weick and K Sutcliffe, Organisational Science, 2006

2) Social Status Modulates Neural Activity in the Mentalising Network, K Muscatelli et al, NeuroImage, 2012

3) The Organisation of Behaviour, D Hebb, Wiley, 1949

About the Author

Dr Norman Chorn is a highly experienced business strategist helping organisations and individuals be resilient and adaptive for an uncertain future. Well known to many as the ‘business doctor’!

By integrating the principles of neuroscience with strategy and economics Norman achieves innovative approaches to achieve peak performance within organisations. He specialises in creating strategy for the rapidly changing and uncertain future and can help you and your organisation.

Subscribe to our regular articles, insights and thought leadership